Alisa Petrosova’s job is to think about how to tell stories about the apocalypse.

“Some people are more concerned with going to Mars than with being able to stay on earth.”

This month I wrote an essay about gossip for the Los Angeles Review of Books, which I’ll be very excited to share when it comes out. I won’t publish it here, but know that your support allows me to keep writing on and off this platform, for which I am deeply grateful! I’ll be spending the next two weeks at the Marble House Project Artist Residency Program where I’m going to attempt an essay about pregnancy, which is a topic I find most writing about to be very, very boring. Pregnancy and motherhood might be the ultimate you-had-to-be-there thing. We shall see. In the meantime, here is another interview with a person who’s brain I find very, very exciting.

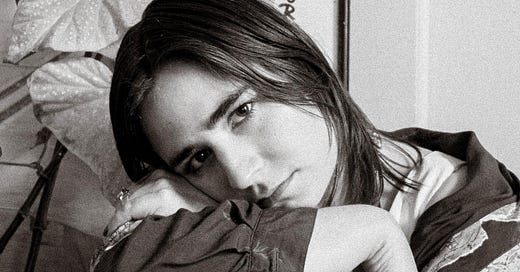

I met Alisa Petrosova at an event last summer at Pioneer Works called Bitches. As far as bitches go (I really prefer the word biotch but I’m all for reclaiming misogynist epithets), Alisa is a very smart (and hot) one. She does incredibly cool work around a topic I am primordially preoccupied with both in the project of this Substack and in life: how to tell stories about the current/impending apocalypse—particularly in ways that will not paralyze people with depression and anxiety but rather get people moving toward a better future.

In addition to teaching at the Climate School at Columbia University and helping students transition into the new climate economy, Alisa also runs the climate research and story consulting program at the nonprofit Good Energy, which works to bring the climate into film and TV. Alisa helps filmmakers tell better climate stories.

Alisa doesn’t just think about how to talk about the apocalypse for a living. She also comes from a double refugee family—half Armenian, half Ukrainian. So the end of the world, or as she says “the multiple ends of multiple worlds,” are very real to her.

I fully and enthusiastically endorse the way she sorts through hope, optimism, pessimism, and futurism and her opinions about what stories people need right now. They’re not what I hear everyone else going around saying, but I really wish they were. So I wanted to share them with you all.

How does your family’s background inform the ways you think and feel and work?

My family is from Nagorno-Karabakh, the part of Armenia where the war re-started. I had that blank optimism for a while––the kind that some people in the climate movement have. Then came 2020 and suddenly, I was watching my community walking out of its indigenous homelands, burning their houses down behind them so the enemy couldn’t move in. My family experienced that in the late 1980s, and then I re-experienced it through the screen(s).

And then in 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. My dad was the only one who left, so whole rest of our family is still there. I wrote about how we got my grandmother to the US through the Southern border during the war. [This is a beautifully written and compelling story that includes some history of the Roma people I never knew about! Highly recommended reading! I read it with my grandma and grampa and my grandpa and I both cried.]

I wrote to cope then and I’m making a film right now about my experience coming to terms with various ends during the pandemic, the solastalgia I experienced, the generational trauma my family carries..

At the time, all the sudden, working on the climate was my optimistic thing, which is a different experience than for most people working on it in the US. But I also have an aversion to stories of hope. I can have as much hope as I want that the war won’t continue, but that’s not going to do anything. Hope is a privilege. I exist in those identities from afar. It’s rational and theoretical for me.

There’s a dichotomy around hope: I don’t necessarily need hope but my relatives need hope to wake up. Who needs to embody it to get through the day vs. when we’re living in the abstract, how useful is it? I’m against it as a broad need for an American audience, but acknowledge that in the day-to-day on the ground, it’s the only way you put one foot in front of the other.

Why do you say “ends of the world” in the plural form? What does that mean?

There’s this biblical Western obsession with the world ending in a unified apocalypse, which is hopeful, because then you don’t suffer. It just happens. And there’s nothing you can do about it. So what’s happening in Palestine, Ukraine, Armenia? The world ends on a daily basis.

For the Armenian diaspora, we’ve always lived after the end of our people—in an ongoing genocide. In Ukraine, they're living through the end of the world actively, because when the war ends, they’ll never go back to the Ukraine they knew before the war. It’s multiple ends to multiple worlds. There have been so many apocalypses.

For an American audience that’s generally out of touch with those realities, if what they need isn’t hope, what is it?

My boss lives on the front line of climate change on the Gulf Coast of Alabama and she knows her house won’t be there year-round in the coming decades. We share the same feeling that optimism is insulting. People in the US—especially white people— don’t tend to understand that. We’re constantly told we need more hopeful stories in the climate space. But what does that mean and what does that do? I’m not saying we only need scary stories that freeze us to our couches thinking nothing can be done, but blind optimism also leaves you on your couch. Hope can make you think “someone else is going to take care of this.”

There’s a lot of people we need to take care of here and now AS we take care of the people in the future. Of course with my family, I think a lot about the future of climate migration and the global north preparing for the influx of climate migrants. I don’t want to say we’re not thinking about it or working on it, because there are a shit ton of people working on it. But they need funding. BUT there are so many current crises. We need to prepare but there’s Palestine, everything Ukraine brought to Europe, and, and, and. Everything needs funding.

During the pandemic, I worked on the show Extrapolations as a world builder and researcher. It’s the first show all about climate, set in 2037, which we chose because it’s the same length of time between when the movie The Hangover came out and now. The Hangover does not feel like a period piece to us today. I got to work with researchers, activists, and people on the front line to build out what the future would look like if we continue business as usual: not investing a ton in climate but not ignoring it entirely either. And most people find it really apocalyptic.

I’m always astounded by the tech community that puts all of its energy into futurism for the sake of futurism. Great, you made goggles that are going to make people more addicted to being in the digital world. But there’s so much innovation that needs to happen. Some people are more concerned with going to Mars than with being able to stay on earth. It pisses me off.

It’s also difficult to constantly be pessimistic. I’m not saying a better future isn’t possible, I’m just sometimes more concerned with the realities of our present.

What are the narratives we as a society need right now, for the present?

It’s not the same conversation about denial anymore. The denialism now is “I’m not going to think about it because it’s too overwhelming.” The mass media rejected Extrapolations because it was bleak. Nobody wants to see a semi-realistic depiction. Nobody wants to believe that that’s what’s to come.

We need stories that promote courage, to fight this face-on. We’re just living business as usual and not feeling the pain of the world. We need narratives that help us process ongoing grief. Instead of processing, we compartmentalize it all as “news” or “facts,” and then go to work and carry on with our days. But showing the actual meltdown or breakdown is really helpful. A good example of that is Jesse Eisenberg’s new film, A Real Pain.

We also need stories that interrogate the hero’s arc and journey where the hero is an individual. We need stories about community and collective action. We think when disaster hits, we’ll isolate or be survivalist––everyone for themselves. But actually, people come together in crisis. And I would argue that we need to come together before crisis. How do we model and show how collective action builds the world we want to live in? We need narratives of care.

A good example of that is Fariha Roisin she writes about her trauma of assault and in the end it’s not man who saves her, it's a multilateral friendship network and ecosystem of a community of women. It’s not about knights in shining armor. It’s about an ecology of people to hold us in the process.

Also, we need to model what kinds of roles there are in building a better world and show that it’s not all policy, science, and activism. Not the individual action story about like… “get solar panels.” We need to combat the stories that people are going to lose jobs to the new economy and show people taking on climate in their regular work, transitioning their careers to be about climate. You can be a baker, a plumber, a doctor. You need to acknowledge, deal with, grieve the climate, and go do something about it.

How did you go from the arts into climate work?

In college at Cooper Union I took an interdisciplinary seminar where we had lawyers, poets, activists, all together concluding that the world was going to look very different soon.

Then came the week when the Kavanaugh trials, the EPA rollbacks, and the IPCC report saying we had about 10 years ‘til we were fucked all happened. And there was this SNL skit, a cold open of Kavanaugh, and watching that, I was literally like holy shit, how the fuck are living our lives business as usual? There was something specifically triggering about this intersection of men historically and presently treating women as property and the same kind of land as property idea that brought on the climate crisis. It was an SNL skit that connected ownership and supremacy for me.

From that week forward, I decided that everything I did would be around climate. It was like Plato’s cave. The shadows on the wall are business as usual. Once you leave the cave, you can’t come back. I couldn’t just work in capital A Art without preparing for the future.

A few months later, an engineering student and professor and I got a grant to bring the climate conversation to campus. We brought in Cecilia Vicuña and Naomi Klein and others to speak in concert with Climate Week NYC and the UN Climate Action Summit.

There was no conversation between climate and Hollywood at the time, so I didn’t think that would be my career. I went to the climate school at Columbia for grad school and I was pretending that this foreign language made any sense to me. STEM seldom appreciates or considers the arts, and in that setting, they just weren’t considered enough. I tried on so many hats, I lost my sense of self. Then I found storytelling. I got connected to Good Energy my last week of school, and it was perfect for me.

It’s important for people to know that you don’t have to leave your field to adapt what they do to the climate. You don’t need to be a scientist or policy wonk to be in climate work. A lot of us are going to have to pivot and use the training we already have and then add onto it.

What are the narratives that are helpful to you personally, as someone with your background and someone who’s staring into doom day in and day out? What helps you keep working every day?

Daniel Kwan, who made Everything Everywhere All at Once said, “systems are fossilized stories.” Maybe there’s no precedent for a climate crisis, but there is a precedent for humans looking at a giant problem and thinking, “things need to change.” I hold to a belief that we can repeat that pattern. We feed climate models stories that are history. The model spits out “if this is what happened in the past, this is what will happen in the future.” If you feed it new stories, you can get better future scenarios out of it.

You can follow Alisa on Instagram and learn more about her work on her website.